Mungalla Station is located in north Queensland, between the cities of Townsville and Cairns, 12 kilometres east of the town of Ingham. This area is the traditional country of the Nywaigi Aboriginal people, who have occupied these lands for thousands of years. Nywaigi ancestral land is approximately the coastal region from the Herbert River in the north to Rollingstone in the south, and to Stone River in the west.

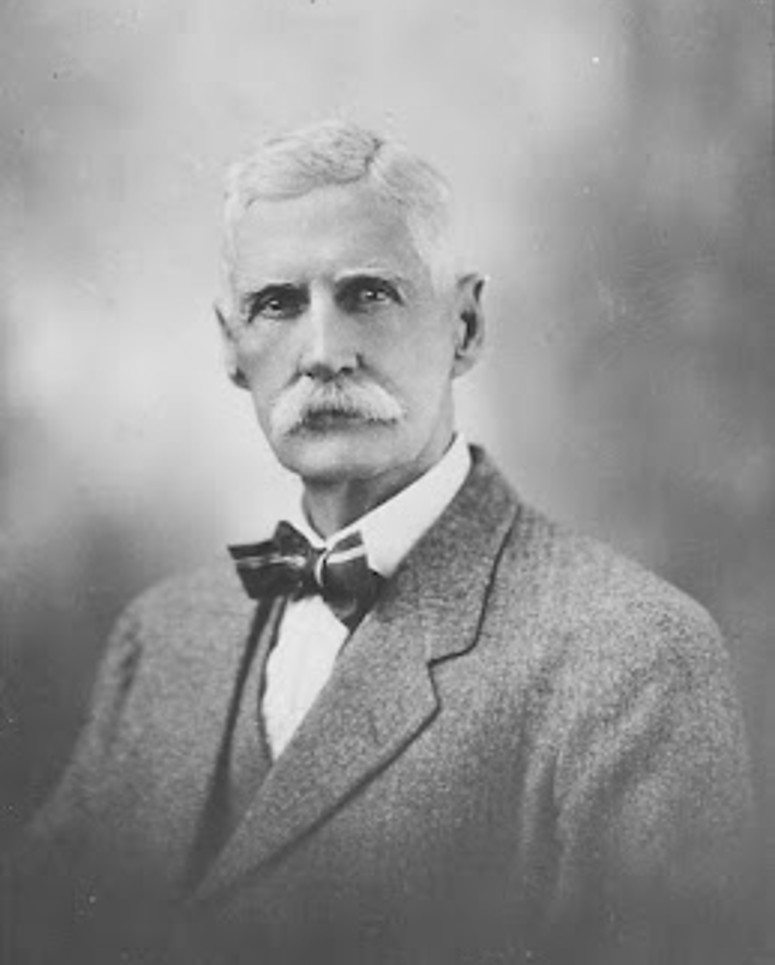

For 120 years however, Mungalla was the property of European settlers. From the 1860s Aboriginal people had been dispersed from the coastal areas of north Queensland as the sugar cane and cattle industries encroached on their traditional lands. The Mungalla cattle property was founded in 1882 by James Cassady, a pioneer of the north Queensland pastoral industry, but he allowed the Nywaigi people to continue living on the property and was a strong advocate for Aboriginal people. However, again in the twentieth century, Nywaigi and other Aboriginal people were forcibly removed from their ancestral lands under government-sponsored programmes. Many were relocated to Palm Island, off the nearby coast, which is not part of Nywaigi country. In 1999, when Mungalla was purchased by the Indigenous Land Corporation, the ownership returned to the Nywaigi people, who now own the 880 hectares that makes up the property today.

The property was purchased to benefit the Aboriginal community financially, socially and spiritually. The Mission Statement of the traditional owners is as follows:

Mungalla Station is a resource owned by the Nywaigi Traditional Owners for the purpose of fostering Aboriginal cultural values by building economic and cultural opportunities through the careful use of our country as a legacy for our children.

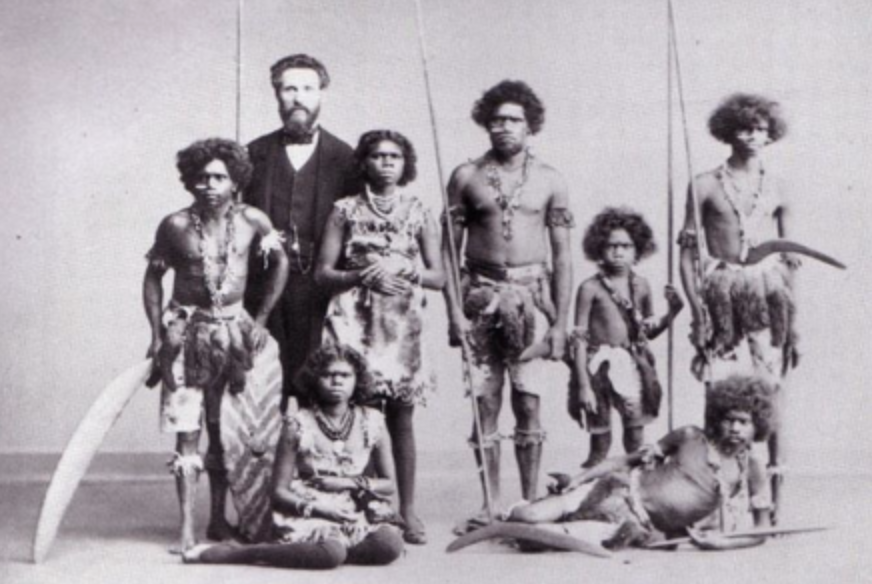

Indigenous Australians are the original inhabitants of the continent and surrounding islands. It is thought that they arrived here over 45,000 years ago. Aboriginal is a name used for the inhabitants of the mainland of Australia and Tasmania, while the people from the islands off the northern tip of Australia are called Torres Strait Islanders. There was great diversity among the different Indigenous communities and societies in Australia, each having its own unique mixture of cultures, customs and languages. It is thought there were over 250 different spoken languages with 600 dialects at the start of European settlement.

During the occupation by the Cassady family, Mungalla was also home to people from the Pacific Islands, Kanakas, as they were called then, or South Sea Islanders. They were originally brought to Queensland to work on sugar cane plantations.

Facebook

Facebook Instagram

Instagram